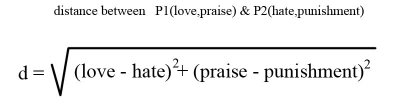

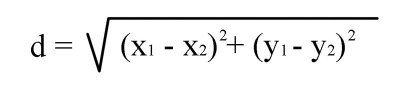

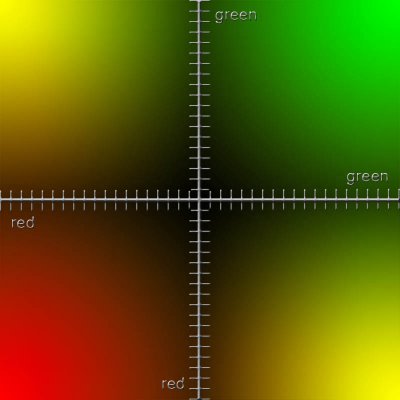

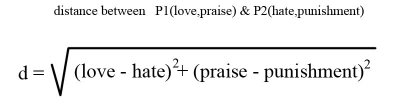

2.7. Distance Formula and Verbogeometry. As we have seen, to calculate the distance between two points, we need to describe our points by its coordinates using the nomenclature of the coordinate pair. Let me reiterate, describing a point in verbogeometry is no different from numerical coordinates except we use words. Lets look again at the example in figure 15 where we used the midpoint formula to find the exact point between the points: P1(love,praise) and P2(hate,punishment) but instead of putting them in the midpoint formula lets put them in the distance formula. (See figure 32)

Figure 32

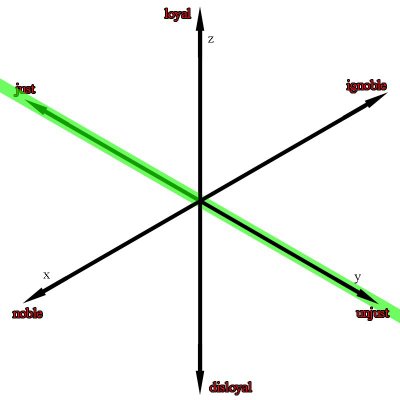

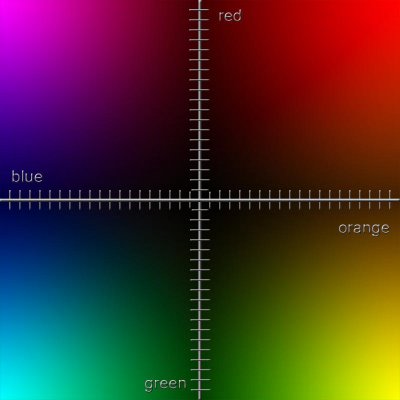

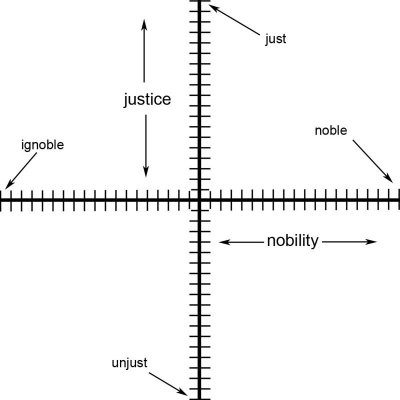

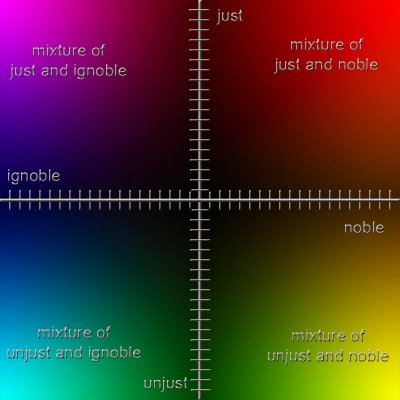

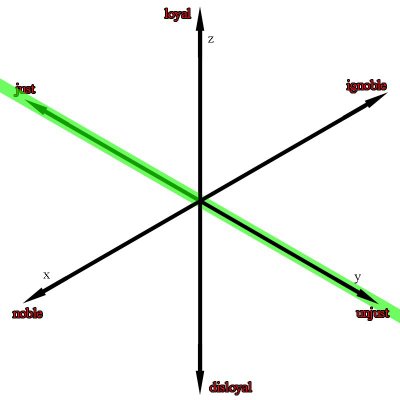

Here we have an expression for the distance between the points P1(love,praise) and P2(hate,punishment) in two dimensions. But we can also use verbogeometry in any number of dimensions including hyper-dimensions. But before we look at hyper dimensional verbogeometry lets look at another example which we will express in the third dimension. The following example uses a three dimensional Cartesian coordinates system with 3 simple antonym word-axes. (See figure 33) The first axis is noble / ignoble the second axis is just / unjust and the third axis is loyal / disloyal.

Figure 33

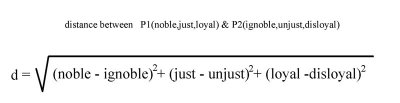

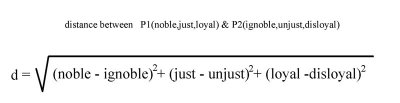

Now lets look at the expression for the distance between the points P1(noble,just,loyal) and P2(ignoble,unjust,disloyal) see figure 34

Figure 34

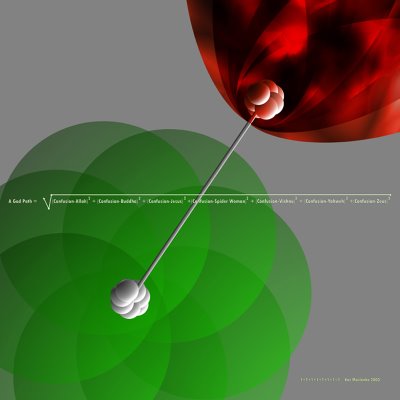

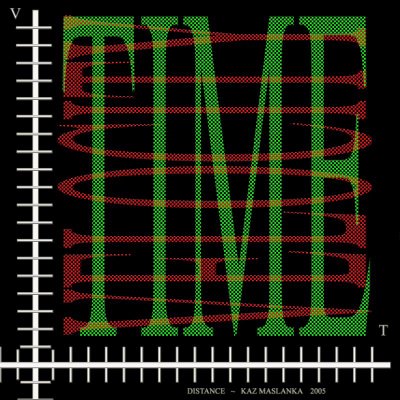

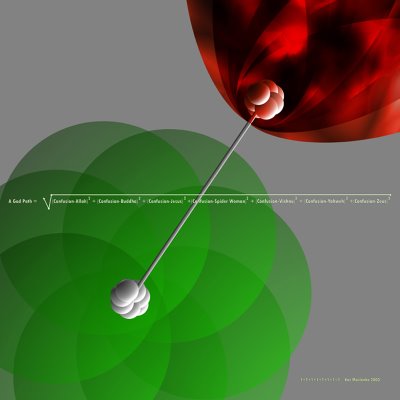

Notice the green line in figure 33 is the visual representation for the mathematical expression above. However, it would be much easier to visualize if we were able to rotate the axis. Figure 33 is an isometric view, which I chose to use because it is best for viewing the axis but unfortunately at the expense of viewing the spatial orientation of the green line.Now let us look at verbogeometry in a hyper-dimension. Let us look at the distance formula used in seven dimensions:Figure 35 shows the mathematical poem 1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1 =1 This is a metaphorical piece that creates a metaphoric path from the concept of confusion, to where seven deities meet. The piece uses the analytic geometry distance formula in a seven dimensional space where each dimension is a gradation from confusion to a point where a deity exists.

Figure 35.

Here is a detail:Figure 35

Lets look at the coordinate pairs for these two points P1(confusion, confusion, confusion, confusion, confusion, confusion, confusion) and P2(Allah,Buddha,Jesus,Spider woman,Vishnu,Yahweh,Zeus)In conclusion what I have shown is scratching the surface of the possibilities of verbogeometry. Verbogeometry can be taken in vast directions that I have not covered or will be able to cover. I hope, in the future, more people join in to explore the possibilities of verbogeometry.

Kaz Maslanka

San Diego, California

February 3, 2006